A major thrust in our group involves the development of novel field theoretic simulations (FTS) techniques for the study of systems that can only be crudely modeled by existing methods. FTS are a broad class of numerical approaches that include self-consistent field theory (SCFT), which is a ubiquitous method for studying polymer melts, blends, solutions, and block copolymers. This family of methods is a highly coarse-grained description of a system where polymers are typically modeled as Gaussian chains with purely local interactions. After writing down the partition function for such a model, one uses a particle-to-field transformation to exactly transform the model to a statistical field theory that can be evalulated numerically on a collocation grid or attacked with a variety of analytical techniques. The advantage of the FTS framework is that one can frequently resolve the model using significantly fewer collocation points in the field theory than there are particles in the underlying model, leading to more efficient simulations.

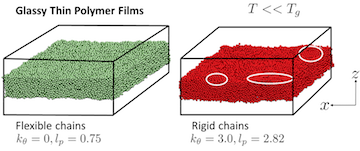

A significant shortcoming of many current implementations of polymer field theory is that they completely miss correlations due to excluded volume, which makes this approach invalid for systems where correlations become important. This includes capturing the packing of monomers near a hard wall, or capturing the manner in which nanoparticles would affect the conformations available to a polymer chain. Correlations are missed because the monomer densities are typically described as point particles (mathematically, the density is defined as a sum of delta functions, \(\hat{\rho}(r) = \sum_i \delta(r-r_i)\)), and the interactions are purely local. A pair potential would be of the form \(u(r) = \chi \delta(r)\), so monomers would only interact when they are precisely on top of each other. This is clearly inadequate if one wishes to include objects such as nanoparticles that are significantly larger than a typical monomer size.

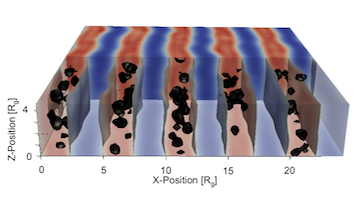

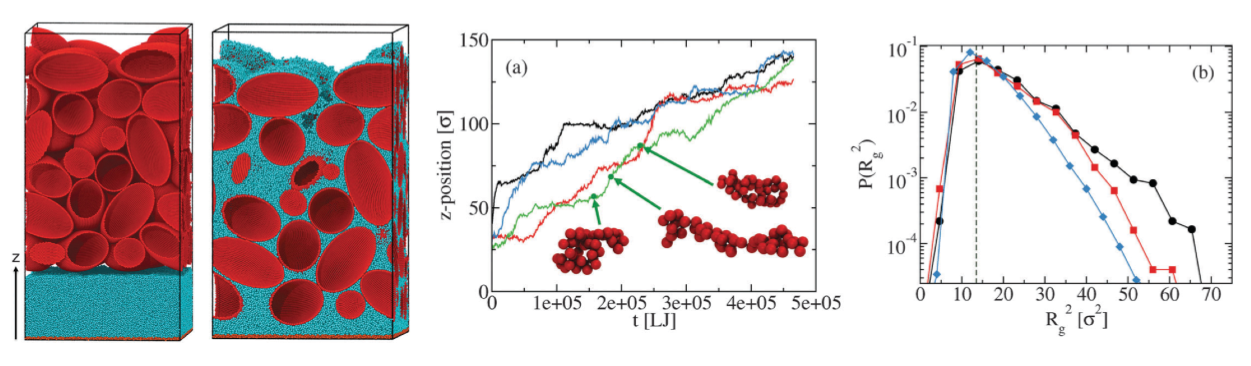

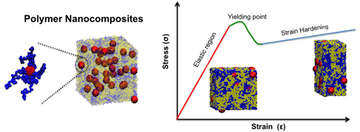

Our approach has been to show that by simply using a “smearing” function that describes the shape of the monomer, we can move beyond the point-particle approximation to include objects of a finite size (e.g., nanoparticles) in our theories. We simply replace our microscopic density function with a sum over these smearing functions, \(\hat{\rho}(r) = \sum_i \Gamma(r-r_i)\) where \(\Gamma(r)\) describes the shape of the object, as shown in Koski et al., 2013. We call this framework polymer nanocomposite field theory (PNC-FT); it is a generalization of the prior hybrid particle/field theory pioneered by Sides et al., and our approach enables efficient study of the fully fluctuating field theory using the complex Langevin technique.

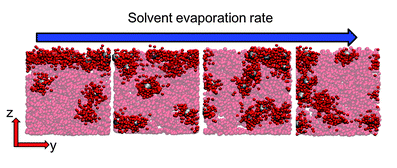

There are few limitations on the choice of the smearing function, which enables us to study a wide range of polymer nanocomposite systems. We typically use a Gaussian distribution to describe the distribution of mass within a coarse-grained polymer monomer and spherical step functions with a soft interface to describe the shape of spherical nanoparticles. It is also possible to employ anisotropic smearing functions, enabling us to study rod- and plate-like nanoparticles. We have also further extended the theory to describe polymer-grafted nanoparticles with arbitrary grafting architecture such as homopolymer grafting, grafting with mixtures of polymers, block copolymers, and Janus grafting, which has allowed us to study the interfacial activity of different designs of grafted nanoparticles and their effect on the interfacial tension in polymer (see Koski et al., 2015) blends.